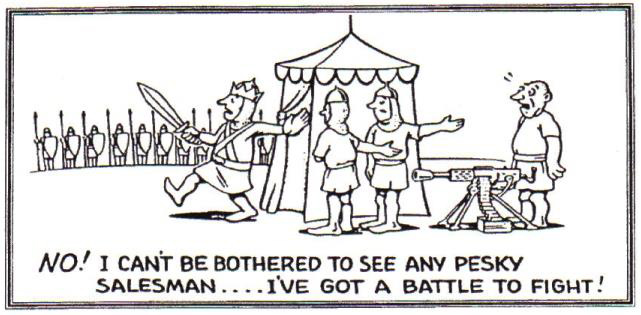

If you've spent any real time on the direct side of procurement, you've likely found yourself listening to a pitch that doesn’t hit the mark for a technology platform or “transformation playbook” that has little to do with the realities you encounter every day.

There is a specific kind of skepticism that settles in during these conversations. It is part earned from experience, part instinct shaped by long nights managing risk and reacting to production constraints. More often than not, skepticism is well founded. Things often don’t add up between your pain and the advertised promise.

But imagine a different kind of pitch that doesn’t attempt to impose indirect procurement logic on the wide-ranging world of direct spend: engineering change orders, COGS, and an evolving supplier base you actively co-develop with versus simply transact with.

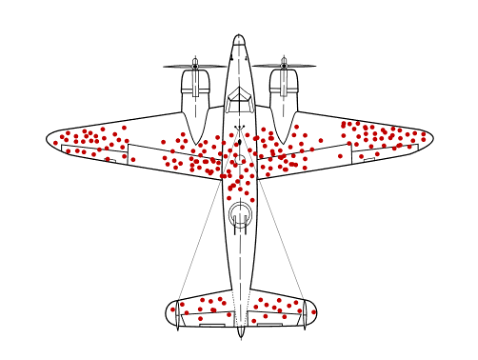

“These are the planes that come back.”

That’s how Tony Nathanson, Global Lead, Direct Materials Practice at RiseNow, opens our conversation on the often-misunderstood world of direct procurement. He’s pointing to the famous WWII survivorship bias example—the bullet-riddled returning aircraft that eventually led engineers to reinforce the right critical parts of the aircraft vs. the visibly damaged ones. Those “still good-looking areas” represented the planes that never came back to base. “What’s really hidden versus what is visible?” he asks. “Are we solving for the right problem by focusing on the ‘bullet-ridden areas' of our challenge? That’s the question.”

The same kind of logic, he argues, applies to direct procurement environments. While procurement tech firms and consulting shops claiming direct procurement capabilities have rushed to digitize the front end of spend management, Tony insists they’re largely missing “the critical parts of the plane.” They’re often attempting to extend indirect procurement tools and processes into the gray area that sits between direct and indirect procurement.

We sat down to unpack the real differences between direct and indirect procurement, the hidden cost levers that most organizations ignore, and the growing relevance of “design to source” for manufacturers trying to reengineer their supply chains under pressure.

Let’s start with semantics. The line between direct and indirect spend isn’t always obvious and often appears as a grey zone adding to the confusion. But Tony offers a sharp filter.

“Can you allocate a cost directly to a particular product or task without ambiguity? Does the expense have a direct impact on the budget, pricing, or profitability of a specific product, service, or project?”

That’s clearly direct. Everything else? Probably indirect. That’s where many solutions overpromise. “You have a lot of source-to-pay players that reach to some extent into the gray space and claim full direct capabilities,” Tony says. Nevertheless, clients with highly complex processes containing a large number of degrees of freedom need appropriate solutions that address operational opportunities across their entire supply chains.

Why? Because direct isn’t just about obtaining the lowest possible market cost for a commodity under optimal commercial terms. It’s about engineering the cost as a priority, step-by-step from idea to production by creating and nurturing relationships, influence, and integration across engineering, operations, and suppliers. The cost is an active and controllable component present early in the design process. Hence, in the direct world, procurement is proactively involved in the design stages as premier suppliers are selected to partner in the development of the product, process, or service.

“Typically, engineering drives how this should be done with close procurement co-piloting. This does not eliminate the need to conduct RFX processes after the design is complete, yet the sourcing exercise is different and holds far fewer risks and surprises. The criticality of the sourcing phase is reduced, and the outcome is co-shared by engineering and procurement,” Tony explains.

Why Supplier-Led Innovation Matters

The supplier isn't just a respondent to an RFX. In direct, they’re a co-architect and co-engineer. Tony gives a story from when he worked with a global auto manufacturer:

“They were ordering engines in batches of ten, which was aligned with their own line throughput. While working with their key supplier on a cost improvement program, the supplier shared, ‘Our production line is built for batches of 14.’ We changed the order structure, flexed the JIT requirements, and cut supply costs by 17%. That only happens when you collaborate deeply.”

This principle scales. The biggest lever in direct isn’t always purchase price; it’s design, manufacturing, and logistics (meaning materials, methods, processes, inventories, equipment, efficiencies, etc.)

Tony poses another example: “I’m making a part out of cast metal that is machined. A supplier comes and proposes a new plastic, composite, or totally new manufacturing process like 3D printing—it’s cheaper, faster, has a smaller CO2 footprint to produce, and works better. If I keep looking exclusively for traditional metal suppliers, I miss the opportunity entirely."

Direct, then, is not just a supply-side game. It’s a design-side game. And it starts with an open door. “You have to give an equal opportunity to suppliers. Not just the traditional ones, but anyone with an idea, even if it sounds counterintuitive at first. ’Unreasonable’ vs. ‘Reasonable’ people are those who most often drive breakthrough change.”

R&D and/or Design to Source: The Missing Link

This is where “R&D and/or design to source” comes in. It's a concept more than a product, but increasingly becoming both. Samsung SDS Caidentia is one of the best-kept secrets leading the charge here, enabling visibility all the way to raw materials and allowing co-engineering between buyer and supplier to jointly develop and finalize specifications to precede a more conventional sourcing exercise.

“You don’t just source a part like a commodity,” Tony explains. “You get involved with the supplier all the way to the raw materials, with necessary visibility and control over the entire supply chain flow sheet.”

The Playbook, Reordered

Tony outlines three classic levers for cost reduction in direct procurement:

1. Leverage back to existing suppliers under new market conditions and cost pressure

2. Re-sourcing: Awarding items to new or existing suppliers

3. Value Analysis/Value Engineering (VA/VE), the most powerful (but most time and effort-consuming) option

And guess which one he says matters most?

“Value Engineering takes creativity, thinking outside of the box, time, commitment, and money. That’s why it’s listed last, even though it’s relatively the most impactful.”

He reminds us that the term didn’t even come from engineering. It came from procurement—specifically from a WWII GE buyer analyzing substitute materials used by necessity that performed significantly better than the originals and reduced lead times and costs.

Why It Matters Now

Post-pandemic supply chain volatility and disruptions, nearshoring, onshoring, and tariff pressures have reignited the need to revisit and up-class direct material strategy. And suddenly, terms like “design to source” matter to the boardroom, since everyone is ultimately interested in TCO and not just a low-cost supply.

Tony leaves us with a few takeaways:

“You need to open the door to suppliers, not just the usual suspects. Listen to your own technical people too. I have not yet met an engineer who did not complain that ‘he/she has such a great idea but no one seems to listen.’ You need to be ready to explore brand new avenues and embrace new concepts."

Direct procurement is a highly interactive and iterative process. It’s not a one-and-done. If you want to do it right, you have to embed yourself. Indirect you may do at arm’s length. Direct, you really can’t.

There is no tech solution, direct or indirect, that takes care of all of a client's needs. You must be ready to bridge the gap with appropriate business processes, technology upgrades, organization design, and skilling of your team.”

So What?

Direct procurement isn’t glamorous. It’s messy, nuanced, and relational. It requires a good amount of soul-searching and vision. But for companies chasing resilience and margin at the same time, in an ever-changing market landscape, it might just be the most strategic lever they’ve got.